Thursday, September 24, 2009

Thursday, September 17, 2009

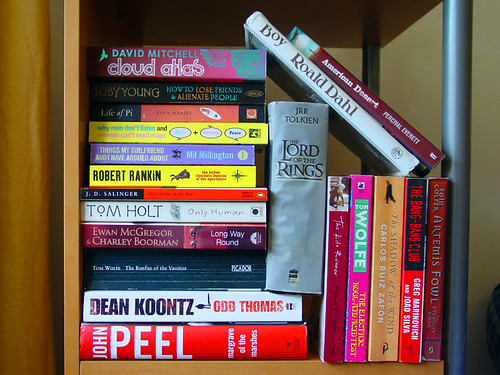

Parallel Importation of Books

(picture licensed under a CC-BY licence from Ian Wilson)

The Productivity Commission has recommended that the laws enforcing the parallel importation restrictions (PIRs) be repealed.

If Australian publishers meet certain conditions, the Copyright Act 1968 effectively bestows upon them a monopoly in the local book market. Booksellers in Australia are restricted from imported a cheaper version of the book, and must buy it from an Aussie publisher instead (if available).

On the whole, this means that Australian publishers wield considerable market power, and arguably make supernormal profits as a result.

I just bought a book from The Book Depository (UK) for $34.40 plus a $2 international transaction fee on my credit card. The Book Depository charges in pounds and does NOT charge for shipping. At the local second hand book store across the road from my office, the same book goes for $40. At Borders further down the road, it's $59.95. Ouch.

Even if you accounted for foreign currency exchange differences, it seems to me that the Australian book retailers are charging a lot more for these books that our overseas counterparts. Presumably, that's because they have to buy it from Aussie publishers. When it comes to the relationship between booksellers and book publishers, booksellers appear to be the price takers.

An interesting quote from the Senator Carr on Printnet reveals something about these margins (or supernormal profits). He says (and presumably the printing/publishing industry agrees) that the margins the publishers make from best sellers are used to invest in more risky and unknown Australian authors. That is, the (supernormal) profits are used to invest in some authors which produce "cultural externalities" which would otherwise not be commercially successful.

Graeme Connelly (CEO of Melbourne Uni Bookshop) reckons "much of the argumentation by publishers (to the Productivity Commission) has frankly been rent-seeking."

Allan Fels made an interesting remark about the (then) Prices Surveillance Authority 1989 report recommending the repeal of PIRs on books. "It made a terrible mistake. It said there were two problems. Never give a politician two problems. Cos they'll take the easy one and solve it. We said that (a) there was a delay in books getting to Australia and (b) the prices were too high."

In 1991, amendments were passed requiring Australian publishers to supply the books within 30 days of publication in order to receive PIR protection. This solved the delay problem, but did not affect prices.

One other thing about Senator Carr: he thinks that the publishing and printing industry should be *tin foil hat on* "protected" *tin foil hat off* because we need the excess capacity in Australia to ensure the maximum dissemination of ideas. That is, despite the internet providing almost no barriers to dissemination, we still need books (and hence the decision makers and gatekeepers, publishers) to get the ideas out there.

I dunno about that, it might be true, it might not be. Something tells me, if we lift the PIRs, although the publishers can kiss some of their supernormal profits goodbye, they'll be just fine.

Let's maximise consumer surplus!!

Saturday, September 05, 2009

The Gospel and Intellectual Property (rival goods)

I've just finished reading "The Future of Ideas", a not so recent book by Lawrence Lessig. It talks about rivalrous goods and non-rivalrous goods.

A rivalrous good is one where my use of the good (say, a car), will rival your use of the same car. We cannot drive it at the same time. Most physical objects are rivalrous to some extent. A public park is non-rivalrous, until it gets really crowded, when my use and enjoyment of the park is negatively affected by your (and the thousand other people) use of the park. It will then become rivalrous.

Intellectual property, and knowledge in general, has the character of being non-rivalrous. If I learn something from you, say a recipe for chocolate brownies, you do not need to unlearn it. My use of the recipe does not rival your use of the recipe. Although, if we shared one oven, hopefully we can use the same recipe, otherwise the use of the oven will be rivalrous!

ANYWAY... I was thinking about the Gospel (aka Good News), and how people tell other people about Jesus. One of the great things about the good news of Jesus, is that, if I know it in my head, I can tell you all about Jesus. I do not need a leaflet, or a pamphlet or a bookmark to tell you about it. Leaflets may be finite (and their use rivalrous), but the gospel itself is not rivalrous. Millions of people tell millions of other people about Jesus all the time, and the gospel will never diminish in it power.

Interestingly enough, one might say that the act of telling people about Jesus, actually enhances my ability to tell more people. Like they say, practice makes perfect. Also, websites tend to be regarded as non-rivalrous, as MANY people can visit a website at a time. Although they do have their limits, as Denial of Service attacks can overwhelm a website by visiting it from many computers simultaneously.

So, non-rivalrous news (the good news about Jesus), from an almost non-rivalrous source (a website) - try Two Ways to Live.

A rivalrous good is one where my use of the good (say, a car), will rival your use of the same car. We cannot drive it at the same time. Most physical objects are rivalrous to some extent. A public park is non-rivalrous, until it gets really crowded, when my use and enjoyment of the park is negatively affected by your (and the thousand other people) use of the park. It will then become rivalrous.

Intellectual property, and knowledge in general, has the character of being non-rivalrous. If I learn something from you, say a recipe for chocolate brownies, you do not need to unlearn it. My use of the recipe does not rival your use of the recipe. Although, if we shared one oven, hopefully we can use the same recipe, otherwise the use of the oven will be rivalrous!

ANYWAY... I was thinking about the Gospel (aka Good News), and how people tell other people about Jesus. One of the great things about the good news of Jesus, is that, if I know it in my head, I can tell you all about Jesus. I do not need a leaflet, or a pamphlet or a bookmark to tell you about it. Leaflets may be finite (and their use rivalrous), but the gospel itself is not rivalrous. Millions of people tell millions of other people about Jesus all the time, and the gospel will never diminish in it power.

Interestingly enough, one might say that the act of telling people about Jesus, actually enhances my ability to tell more people. Like they say, practice makes perfect. Also, websites tend to be regarded as non-rivalrous, as MANY people can visit a website at a time. Although they do have their limits, as Denial of Service attacks can overwhelm a website by visiting it from many computers simultaneously.

So, non-rivalrous news (the good news about Jesus), from an almost non-rivalrous source (a website) - try Two Ways to Live.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)